How to Create Your Unique Leadership Style

One of the last things I want to hear about at happy hour is your “love language.”

For the uninitiated, “The Five Love Languages” was popularized by Gary Chapman’s 1992 book of the same name. They are the ways in which we “express and experience love” – words of affirmation (saying nice things), physical touch (a good back rub), acts of service (emptying the dishwasher), quality time (date nights), and gifts (an airport mug from Phoenix).

My issue with the love languages is that they're not "types." Craving physical touch from your girl or wanting Tom to pick up his socks for you aren't unique to your personality. These "languages" are merely behaviors of loving relationships.

It’d be like writing a book called The Five Health Languages and asking, "Which one are you: Nutrition, sleep, stress, hydration, or exercise?"

All five are crucial. None are unique to the individual but common to humankind.

But the love languages stick because we can’t help ourselves. We love carving out neat boxes for ourselves. Giving ourselves a “type” – whether that be Myers-Briggs, color wheels, Enneagrams, horoscopes, or love languages – helps us navigate the very complex, dynamic world of human psychology. When we have a "type," we not only feel a sense of clarity around who we are, but have a road map for how to think and act. Every workshop I do, people can’t wait to tell me their personality type or their communication style.

When we have a type, it allows us to feel unique in a sea of 8 billion others.

So today, after spending 300 words poo-pooing the typing game, I’m going to enter the ring. I’m going to try to toe the line between my aversion to "Which one of these 6 are you?" and the importance of carving out an identity; a style of your own for leadership. I'm going to lay out a framework for you to discover and develop your unique leadership style, without boxing you into one of 5 categories.

And then some other punk can start their Substack article by poo-pooing my ideas before introducing their own.

The Bruce Lee Principle

A mentor of mine, Dr. Jade Teta, once taught something he called “The Bruce Lee Principle” to help people understand and navigate the complex and individual nature of metabolism.

The martial artist and actor Bruce Lee once said: "Absorb what is useful. Discard what is not. Add what is uniquely your own.”

Dr. Jade used this quote to help people find a diet that works for them. I like the Bruce Lee Principle in leadership too.

One of my favorite things about psychology is how textured our minds are. We all have unique psychological fingerprints—distinct in our own way. And that makes sense. We’ve all walked different paths.

Psychologist Kurt Lewin called this Field Theory – the idea that all behavior is a function of a person and their environment. Our emotions, impulses, habits, and thoughts all emerge from the difference experiences we’ve encountered. Who your parents were, the town you grew up in, the experiences you’ve collected have all converged for you to be you. Even siblings won't have a perfectly replicated field.

It's critical that we acknowledge these differences because a leadership style that fits one person well will fit another like high-water khakis (and nobody rocks those well).

That means we can’t just say, “There are three leadership styles, pick one.” That ignores the reality that there are infinite styles. We’re all complex and unique, and the job of a leader is to identify and cultivate their own approach.

This is where the Bruce Lee Principle comes into play. When developing your leadership style, the most important factor is discernment. Take things from leaders you admire. Ignore the things that don't resonate with you. And then add your own unique take on it.

Martin Luther King Jr. took his nonviolent approach directly from Gandhi and applied it to American civil rights. He learned to be a great orator from his father, who was a preacher, but was more skeptical of religion than Martin Sr. He wore fancy suits, studied Karl Marx, loved women and dancing, and saw voting rights as the most important achievement of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement.

Borrowing from others, leaning into our natural proclivities, and knowing there is no one-sized-fits-all approach to leadership is how we begin to build our leadership style.

But when there is no right way, and there aren't only five languages to choose from, what do we do? How do we identify and develop our unique leadership style?

Formulating Your Leadership Style: 3 Elements

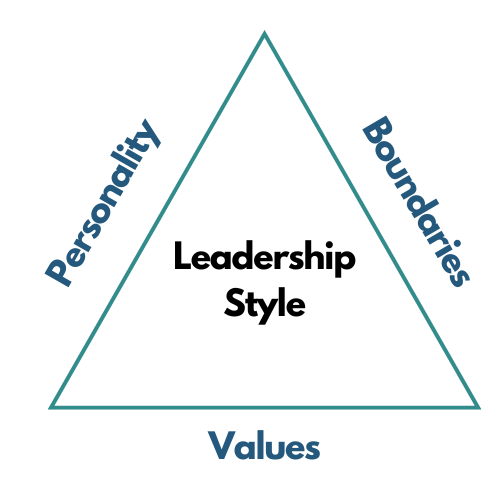

In order to create our own leadership style from infinite avenues, we need a framework. The lens in which I like to help leaders evaluate and discover leadership styles is through a triangle. There are three areas in which we need to explore and define to create our style. Let’s start with the base.

1. Quit With the Vanilla Values

Author and Navy SEAL Mark Divine tells this story from his time in Officer Candidate School.

His sergeant barked, “What do you stand for, Mark?”

“Justice, integrity, leadership,” Divine replied.

The sergeant shot back, “I didn’t ask for your vanilla values, son! What are your rock-bottom beliefs—those you won’t be pushed beyond? Don’t just tell me what your family or society thinks you should believe in.”

Too many of us have “vanilla values.” Those “principles” and beliefs adopted from society that have no emotional charge to them. They’re the beliefs we think we “should” have.

Values aren’t just cutesy words we slap on a wall. They’re the living, breathing expression of who we are and what we stand for. Values aren’t the deep-seated beliefs that guide our choices, behaviors, and judgments.

Most of us never consciously curate our values. They're just handed to us by Mom or Uncle Dave. The Indian philosopher Osho once said: "Your whole idea about yourself is borrowed—from those who have no idea who they are themselves.”

The first step in defining your leadership style is articulating your own values. Values that are real for you.

Values that are put to the test every day in the world. You can borrow and adapt values from others—but only if they fit.

The research on values is overwhelming. Leaders who know and live their values are more resilient, empathetic, and have more self-control. They feel more powerful, perform better under stress, and even have a higher pain tolerance. Writing about values has been shown to boost GPAs, reduce doctor visits, improve mental health, and even support weight loss and smoking cessation.

One study found that training employees on character traits (discipline, integrity, productivity) paid off much more than training cognitive skills (accounting, finance, sales). The "character skills" group saw 30% more profits than the cognitive skills group over the next two years.

Values offer leaders a different scorecard to operate from. We can’t always control the results or other people. Values give us an internal scorecard that allows us to rest easy at night, even when the walls are caving in around us.

I always start leaders off with three questions to help them articulate their values:

Who do you admire?

Admiration often signals what we care about. When you think about the people you admire, what are the traits that stand out? What qualities would you like to embody?

Who do you judge?

Judgment is another place values like to hide. If I judge somebody for being rude to a server, it’s likely because I value kindness.

Does it work?

Lastly, we need to adopt values that nudge us toward our goals. Even "good" values, like honesty, might need to be reevaluated. I've seen leaders weaponize honesty to the point it becomes cruelty. They say, "Well, I was honest," as if that frees them from any accountability. If you're honest to the point that nobody wants to work with you, that's not useful.

2. Personality

If values are the protein and carbs of our leadership style, personality is the seasoning.

My stepmother has been a nanny for infants and toddlers for 40+ years. One of the hills she’ll die on is that each child comes with a baked-in personality. She always says: “You can see their little personalities right away.”

Call it nature or nurture, we’re all wired a bit differently.

When developing a leadership style, it’s crucial to pay attention to some of our natural tendencies. I look at personality through two lenses:

First, our preferences. When I conduct workshops, I ask people to write down an aspect of their work that they’d pay someone else to do on one side of the page.

On the other side, they write something they’d do for free. Or even pay to do the task. The overlap is nearly perfect—someone’s dreaded chore is another person’s “I kinda like it.”

At work, I love building things, working with small organizations, being autonomous, and working with spreadsheets. Yes, spreadsheets titillate me.

I strongly dislike day-to-day management, repetitive tasks, bureaucracies, and marketing.

Knowing your preferences ensures you’re leaning into your strengths, delegating what drags you down, and operating in your zone of genius.

The second piece of personality is our stress response. When the pressure rises, how do you react? Do you go into fight mode and become short with people? Do you enter “flight” and avoid the work you know you should do? Do you freeze? Fawn (start appeasing everyone and get out of conflict as quickly as possible)?

Understanding what triggers our stress response and how we react can help us build buffers into our environment.

For me, I get irritable, Chipotle cravings hit, I zone out with sports, procrastinate on creative work, and pour a nice glass of red. So I set up guardrails—delete emails instead of stewing, keep wine out of the house, block time for creative work.

The point isn’t to eliminate stress—it’s to design your environment so your natural tendencies don’t sabotage you.

3. Boundaries & Rules of Engagement

Chris Paul, the greatest point guard of all time (don’t @ me), was once benched in college for being one minute late to the team bus. His coach, the late Skip Prosser believed that, “If you’re not early, you’re late.” He didn't care how talented you were. Everybody was beholden to the rule.

Tom Coughlin, the Super Bowl–winning coach, had the same rule, starting all meetings 5 minutes early and fining players (even future Hall of Famers) for breaking the rule. Coughlin had all sorts of isms. Apparently, he wouldn't allow his assistant coaches to wear sunglasses on the sideline. Coughlin saw it as a sign of weakness that "prevents another man from looking you in the eye." Hardcore.

Great leaders have rules of engagement. They have clear, strong boundaries that they hold themselves and their teams to. You don’t have to be as rigid as Coughlin, but you do need to have some rules to the game that guide behavior.

The first rule of Fight Club is don't talk about Fight Club.

MLK had non-violence as a nonnegotiable. Legendary basketball coach, John Wooden policed how his players tied their shoes (to avoid blisters). Admiral William H. McRaven makes his bed, Mother Teresa did "small things with great love,” and author Stephen King write 2,000 words a day. The rule matters less than having them.

Leadership isn’t about perfection. You'll never act in line with your values 100% of the time. Your personality will change over time. Rules can have a shelf life.

My personal hero, Martin Luther King Jr., was a complex man. He was courageous, intelligent, and practical, but also highly empathetic and introspective. He was also susceptible to passing moods, was riddled with self-doubt, and craved his father's approval well into adulthood. He loved a good haircut, a nice suit, and women. Integrous in many ways, and flawed in others. Historical figures, they're just like us.

But he achieved great things and left the world better than he found it. And that’s all we’re trying to do as leaders. Not be perfect. Not ignore the flaws of our human nature. But simply leave the world slightly better than we found it, no matter how small an impact that is.

Love this!

“Your whole idea about yourself is borrowed—from those who have no idea who they are themselves.”